Buggy VR: VR Racing Design (until COVID-19 struck)

Buggy VR was going to be a mixed reality based racing game that celebrates 100 years of Buggy history, a Carnegie Mellon tradition where student-led teams compete with aerodynamic, engineless vehicles known as “Buggies.” In partnership with the Buggy Alumni Association, this was intended to be released during Carnival (a Carnegie Mellon April event ) as a mixed reality installation, with a VR game (through Oculus Rift) and a physical “ride” for players to “drive” in. I was the Art Director on this project, but I also helped the Design team with tasks such as user interface designs, gameplay ideation, and user testing. This blog post will cover the design aspect of the VR side of the project.

Unfortunately, due to the COVID-19, Carnival was cancelled, and due to difficulties with testing during quarantine and the decreased interest in a mixed reality game due to safety concerns in the pandemic, we decided to shift gears and turn Buggy VR into a browser based racing game.

Challenges

How do we make the mixed experience, especially with a constrained view like in buggies, comfortable, and immersive?

How do we make a mixed reality experience that anyone can play, regardless of age (the people who enjoy buggy range from college freshmen to >50 year old alumni)?

Should this be a “buggy experience” or be a “buggy game”?

How do we display 100 years of Buggy information in a meaningful way?

Objectives

Create a compelling experience that provides the player with the same sights and sounds as a Buggy driver.

Bring the player through 100 years of Buggy history.

Takeaways

People in a racing game like to be in control, as opposed to an on-the-rails experience.

Having a physical cockpit gives a frame of reference for players to get accustomed to their surroundings.

Always have a backup plan (especially if a pandemic interrupts your project…)

Prototyping in 3D is vital to gain a better understanding of user experience in VR.

Outcomes

Working VR prototype where a player could drive through the entire racetrack.

Extensive playtesting with multiple users.

Unfortunately, a pivot away from mixed reality due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Team

Members of the project, especially in the Design Team, can be found here. Although I led the Art team, I also helped out where I could with the designers, especially due to my experience with 3D prototyping.

Project Objective

Early planning of the game.

Approached by the Buggy Alumni Association, Thomas Corbett was tasked with building a buggy experience for Carnival 2020. In the form of a class (Advanced Game Studio), about 24 people came together to work in what was essentially a small game studio, Strike Force Studios. The goal was to give players a chance to experience being a buggy pilot first hand, an opportunity many people do not have. Although many people have attended the buggy races, less people have participated directly in the event, and even fewer have ever driven a buggy.

The plan was to create a mixed reality experience; the player would sit in a physical installation while wearing a VR headset (the Oculus Rift in our case). We wanted to maximize the immersion for the players, but this brought up major questions that needed to be considered:

How can turning the vehicle be done in such a way to be the least nauseous to players?

Will this be an experience of the race, or will it be a racing game?

How would we incorporate 100 years of buggy into this game?

Limitations/Considerations

Before we could set about designing the experience, there were several guidelines that were established, either dictated by the client or from our own research:

We are basing buggy seating on older buggies. Modern buggies require drivers to lie down on their stomachs.

Players cannot crash or collide with the other buggies (this was dictated to us by the Buggy Alumni Association).

The Buggy cannot stop, and is always in constant motion.

The player must be seated upright, or leaning forward.

Although buggies nowadays are typically driven while lying down, this could lead to discomfort amongst people who have never driven before. We decided to have players sit upright, which drivers in the early days of buggy did!

Research

Examples of games we reviewed.

A lot of research was done on other VR racing games, including Mario Kart Arcade GP VR, Kart Kraft, and VR Karts. Based on our research, we determined that:

avoid VR Motion Sickness, especially with “zooming” in or out effects, bumps in the road, and rapid tilting/bobbing.

control schemes ranged from grabbing the wheel with your controllers, having the wheel be in the shape of a console controller, or use one hand to control the wheel and the other hand to use powerups.

some games built the UI into the cockpit, either in the windshield or in the dashboard.

A screenshot of the game Assetto Corsa, in which the steering wheel resembles the player’s controller.

The Buggy Experience

In order to get our Buggy experience as authentic as possible, we sent out surveys to people who participated in Buggy, either as drivers, pushers, buggy builders, or anywhere in between. These surveys were used to gauge what aspects of Buggy were the most memorable (the survey was created by Nicole Chu, a Buggy brought on as our expert). From the surveys, we determined that:

Specific points in the track (the chute, top of hill 2, and the finish line) were the most exciting moments (especially hearing and feeling the finish line)

The countdown especially was exciting, when people start to cheer as you get close to starting.

The road is very loud!

Though for comfort concerns some aspects could not be implemented, we at least could understand the spirit of the games.

Goals

Based on preliminary research into other VR racing games, we settled on a set of “design goals,” to create a framework which would guide the game’s development, no matter what form it would take.

Intuitive Controls - Bridges Buggy enthusiasts, VR aficionados, and new users

VR Fun Ride - Well-executed, replayable, and appealing to many audiences

Contextual - Incorporates Buggy content and lore

Authentic to the Buggy experience

Lead Game Designer Adela Kapuscinska discussing the Design Goals.

Cockpit Design (Diegetic vs. Non-Diegetic UI)

Diegesis is a way to label a game element in relation to the fourth wall. Diegetic UI exists in the realm of the game’s world. Non-Diegetic UI exists only to the player, or on the other side of that fourth world. There was a lot of discussion about how to represent the UI of Buggy VR to the player. Should the UI be floating in the environment, almost as if attached to the visor of the player? Or should it be affixed to the buggy’s cockpit, like a car’s interior?

After reading certain papers and blogs on VR space design, especially in regards to cockpits (sources include Effect of Design Changes of Automobile Cabin in the Virtual Reality Space, Leapmotion’s studies into VR-Cockpits, and this Medium post on VR user experience design), what I learned was:

Some cockpit designs that I made.

People felt the space was sufficient when they had an increase in roof height and windshield depth (roof height especially).

Use lights, color, and audio to grab the user’s attention.

It’s a lot like theatre, and the player is the star who was not given the script!

Make sure to test with multiple arm reaches and heights.

If possible, have a setting that allows the player to set their height.

Animations can help pop out the UI (curvature also helps give them physicality).

The player’s sight and reach should give them agency on what menus appear.

A near-field frame of reference, like a cockpit or the interior of a dashboard, can help reduce nausea.

We made a few designs for the cockpit, based on external references as well as what made sense in the context of our game. I translated the popular designs into 3D so that we could implement them into our game for testing.

Cockpit designs created by Jaeyeon Huh and Jisoo Shon.

Control Schemes

Although Buggies usually do not come with steering wheels, we wanted to explore different control schemes (rationalized in-universe with the explanation that this was a state of the art buggy). We implemented Bike Handlebars, Levers (to turn, pull the corresponding lever), and a Steering Wheel into our prototype, so that we could test out which control scheme felt the best.

Spectator Mode

In order to address the desire to insert Buggy’s history into the VR game, aside from using historically renown buggies as competitors, we also planned to implement a spectator view for people at the installation who weren’t playing to watch. This view, aside from giving spectators a chance to watch the virtual races, would also have overlays talking about the history of Buggy. Cameras would be placed in the game engine that corresponded to real life camera placement when real Buggy was filmed, and would hopefully provide Buggy education to the viewers as they watched the virtual races.

Playtesting

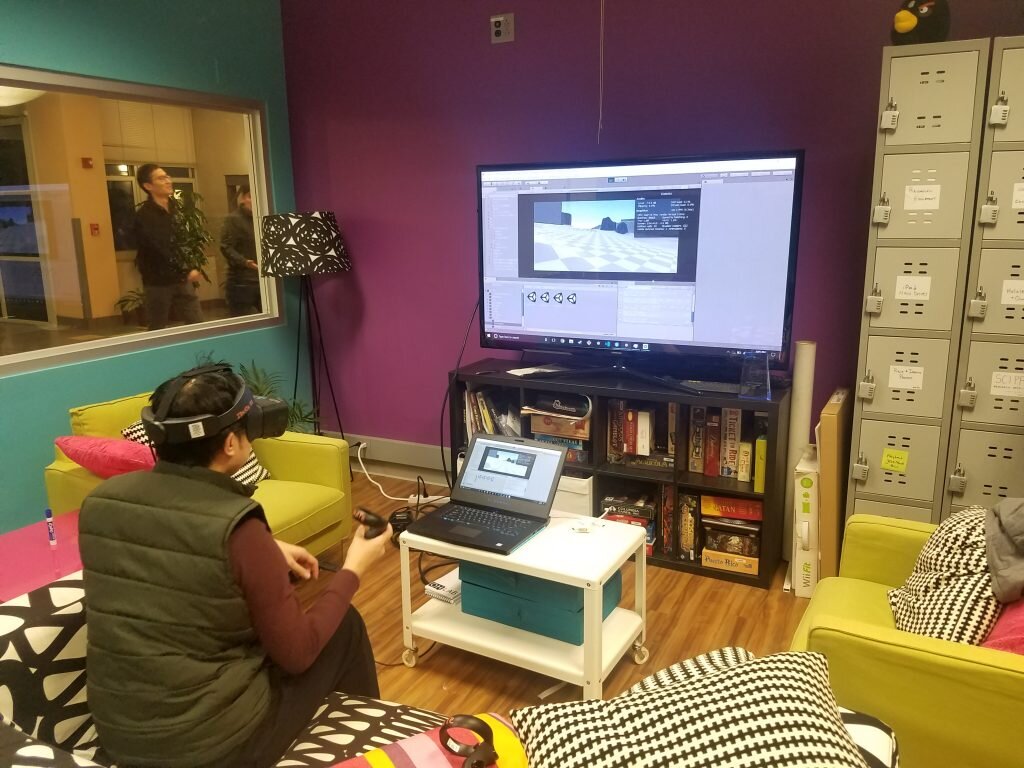

One of our playtesters leaning while driving in our game!

Weekly, we would try playtesting our game in order to see what was exciting versus what was uncomfortable. We would use that week’s build, as well as a post-gameplay survey, in order to gain insights into our game experience. In these sessions, we would have:

The Technician: ran the computer, set up the VR headset, and identified any game-breaking bugs.

The Wrangler: helped the “naive guest” with getting used to a VR environment, especially if they have never been in one before. Also made sure that the player didn’t run into or trip on anything.

The Designer: directed the player in the game, gave them context for aspects not yet implemented, and asked them questions about their experience.

We playtested a multitude of people, from current students to Buggy enthusiasts to even alumni! We wanted a diverse group of testers, and we made sure to mark down their age, amount of experience with Buggy, as well as their experience level with VR. We would bring them into the VR world, give them context on what they were playing, guide them through the game (answering any of their questions while asking a few ourselves), and after they played we would ask them a list of questions about their experience. We were able to glean the following:

Experience vs Game: On-the-rails motion does not feel good - we didn’t want players to stray far from the course, or get stuck on the side. However, we may have laid it on too strong. The gameplay was essentially a train that ran through the course, and players expected to have freedom and control. The realization that they didn’t broke their immersion.

We fixed this by implementing a weaker course-correction system. We allowed players to drive freely, but if they strayed too far from the course, there would be a subtle push back to the main path. Much of this was subject to adjustment based on player feel.

Control Scheme: The Steering Wheel - we tried each of the different controller schemes and asked players how they felt with each one. Though there were a mix of responses, the steering wheel, according to playtesters, was the most intuitive.

Map Design - we tried both a 1:1 scale map of the course, and shortened one (in case the game felt too long and boring). After playtesters tried both of them, there seemed to be no preference.

Cockpit Design - we tested a mix of cockpit designs with various UI elements (such as the timer or minimap). Cockpits were received favorably compared to no cockpits, but the cockpit design so far was inconclusive. Textures needed to be developed to receive better results.

This is me testing out a game build!

We aimed to make further iterations on our game, based on the feedback we received. However, the COVID-19 pandemic prevented anymore progress in the virtual reality front. We could not playtest nor develop the game due to many students having gone on spring break, and thus having no access to VR headsets. In addition, having multiple people use the same VR headset was no longer possible due to fears of COVID-19. The nail in the coffin was Carnival, the event we were building the experience for, being cancelled. Thus, the decision was made to pivot development to a browser-based game, which you can find more information on here.

Thoughts

Although the game was ultimately cancelled, it was an exciting delve into the challenges of designing for vehicular motion in VR. There were so many things that could go wrong, so we made sure to carefully design a comfortable yet compelling experience, which required tons and tons of playtesting. We learned a lot about how to make someone comfortable in a vehicle while in VR and what players want to do when they drive. For me, it showed me how my ability to work in 3D can help affect the user experience and immersion of an application, especially since I built the cockpit in 3D! In addition, this project taught us how to quickly change to a different goal once an uncontrollable event made our current goal unattainable.